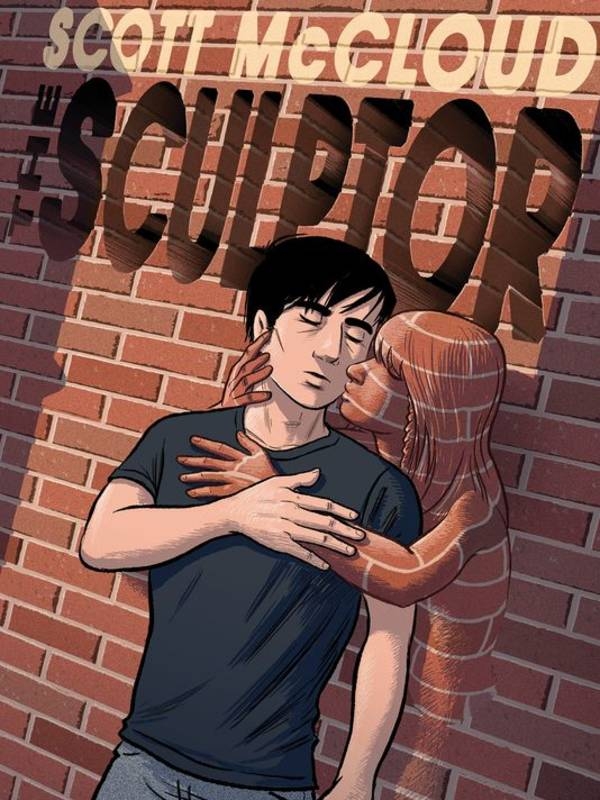

Scott McCloud and Dan Berry talk about how Scott got into comics, the artistic potential of comics, getting the urge to do something and letting his story The Sculptor incubate for 30 years. The Sculptor is out on the 3rd February from First Second in the US and Self Made Hero in the UK.

Dan Berry: This is Make It Then Tell Everybody. I’m Dan Berry. I spoke to Scott McCloud about getting into comics and the artistic potential of comics, getting the urge to do something and letting his story The Sculptor incubate for 30 years. This is Make It Then Tell Everybody. Hey, Scott McCloud, how are you doing?

Scott McCloud: Pretty good Dan.

DB: Pretty good, pretty good.

SM: Pretty good. Extremely good.

DB: That is an upgrade. Well done! We met, I think for the first time in 2011 in Finland.

SM: Yeah, that’s right.

DB: But I spoke to you on the phone when I was… I think it would have been about 2004. I was working on my undergraduate work into interactive comics and I rung you up to ask you some questions.

SM: Wow, I forgot about that.

DB: [laughs]

SM: Oh my god!

DB: Yeah, that was a long time ago.

SM: 2004, that was another world, wasn’t it?

DB: That was more than an entire decade ago.

SM: Yeah, ten years ago we were sitting around thinking how long the internet had been around. Like, how old webcomics had become.

DB: Yeah, oh my Lord. Incredible!

SM: We’ve made so little progress.

DB: We just have podcasts, that’s the only difference now.

SM: Right! [laughs]

DB: And they’ve turned into the most valuable online commodity there is as well.

SM: I think so!

DB: I mean financially and culturally. In so many ways they were the pinnacle.

SM: They pretty much rule the world. Without podcasts society would fall apart at this point.

DB: They’re pretty good. I know I’m biased, but they’re pretty good. So, I remember when we were in Finland, there was a conference on education I think, and we were both giving talks. We went out for a meal, and I remember we were sat at this meal and behind us in the restaurant there were a couple of guys playing chess. And they were doing it really, really quickly, and you said, ‘Oh, those guys are really good at chess.’ I said, ‘Oh, because they’re doing it really quickly?’ And you said, ‘No.’ [laughs] And you explained what it is about chess and you blew my mind. Chess is an entire world that I know nothing about, and I know this might be a strange question to lead off with. You know, a guy who’s done some really good comics, but Scott, what is it about chess? Because chess was going to be your other career, wasn’t it?

SM: Yeah, when I was 13, 14 years old I would have told you my goal was to become World Chess Champion. It didn’t quite work out.

DB: [laughs] Evidently!

SM: No, but I went three straight years of pure chess. I was really obsessed with chess. The way it worked was, when I was a little kid I would have obsessions that would last for maybe a year. There was the Space Program, there was mineralogy. For two years I was going to be a microbiologist. This is elementary school now, we’re talking. Chess was sort of, from elementary school to middle school, and that was three years. I think of that as the first grand obsession. There were the smaller obsessions and then there was the grand obsession. Chess was a grand obsession. Then it didn’t quite pan out for me. I didn’t quite have the talent, and while still in the throes of chess, Kurt Busiek, who I met in middle school, who of course also writes comics today, that’s when he got me into comics, and I just transitioned and became obsessed with comics, except that one stuck, because that one I was able to make work for me.

DB: So he’s responsible for all this then.

SM: Oh, totally. He really is, because Kurt got a lot of resistance from me, because I had a lot of prejudice against comics.

DB: Oh, how so?

SM: So he had to work hard to get me to read the stuff. So, that says to me that without Kurt there, we have a pretty good idea that I wouldn’t be doing what I do today.

DB: That’s really interesting. What were your prejudices?

SM: Well, I thought they were dumb. Some friends had superhero comics, like Batman comics and things like that. I was reading real books. I was beginning to get interested in fine art and I was really into surrealism as a kid, and I looked at comics and they just seemed kind of crudely drawn and badly written and silly. It’s not that I was wrong exactly.

DB: I mean, there are some really dumb, silly comics out there.

SM: Yeah, there really were.

DB: Even today. Even in today’s modern world, there’s some dumb stuff out there.

SM: It’s Sturgeon’s law, you know. It’s 95% crap, or 96%, or whatever his number was. But still, Kurt gave me these stacks of old X-Men and Daredevil and, I don’t know, I got hooked and about a year later, I was 15 years old when I said, ‘That’s it, I’m going to make comics.’

DB: What made you jump from being a reader to a creator then?

SM: I always was going to make something or do something. I was always very proactive. I drew for fun. We started out by doing this weird little role-playing game that had superheroes in it, but it also had things from old TV shows like The Prisoner. It had that big white ball, Rover, from The Prisoner.

DB: Of course, yeah.

SM: And references to The Goon Show and Monty Python. He had a bunch of Goon Shows on old reel-to-reel.

DB: He’s fallen in the water, of course!

SM: Right, exactly! ‘He’s fallen in the water!’

DB: [laughs]

SM: So we had this really weird role-playing game and we would do drawings for it. We would draw characters, and some of them were superheroes, and I started getting into drawing the superheroes. Then I just started to do actual comics, and that was it. That was it. It took about a year and I just plunged headlong. I remember there was an old Jim Steranko X-Men that I was reading in a friend’s house where even as a little kid, I was like, ‘You know, I see some artistic potential in this art form.’ Because Steranko was using these cheesy Salvador Dali effects or something, that to me looked like actual art. So even then, even as a little kid, it was not so much that, ‘I want to draw like these guys,’ it was more like, ‘I see that there’s something you can do with this art.’ I was a very pretentious kid, and it didn’t wear off.

DB: [laughs]

SM: It stuck.

DB: So you failed to progress.

SM: I failed, yes completely, to discard my pretentions.

DB: A lot of the people I talk to, they got into making comics professionally in two ways. They’d either go off and show their portfolio to a bunch of people, or they would make comics until someone said, ‘Hey, you make comics. Do you want to make comics for us?’ Was either of those your experience?

SM: It was the former, but there’s a reason, and it’s because I’m just old enough that the ladder wasn’t really available to us. When we were starting out, the only way that we could conceive of to get into making comics professionally was to go through the big publishers, which were all superhero publishers. So yeah, we worked on our portfolios. But, you know, I was about to leave college and my teacher, Murray Tinkelman at Syracuse in New York, he was tennis partners with Will Eisner, and I remember he set up this meeting with Will Eisner for right as I was leaving school. I managed to get a job in DC Production right before I left school. Three weeks before I was done with college I had this job in New York, working in the production department of DC. So, I was going to be in New York and Murray, my teacher, he arranges for me to meet Will Eisner. I remember showing Will Eisner my portfolio, and I had some of my comic samples, but it also had a lot of my illustration work from school. I remember he was telling me, ‘You know what? This stuff is more interesting.’ He was looking at the illustration stuff, the stuff that I was doing that was just experimenting with different art styles. He said, ‘This is more interesting,’ than basically me trying to imitate Neal Adams or whatever, you know? He was pointing me in that other direction, which I thought was… and I was already starting to maybe lean in that direction myself.

Kurt and I had actually tried, even while still in school to bring stuff down to the majors and see if we could ship around our portfolios and our script samples, and of course we hit a brick wall. In a way maybe it’s good we did, or maybe it’s good I did. Kurt eventually broke into that world. But the model of just make it and tell everybody was not a… in the late ‘70s, early ‘80s, you see, that wasn’t really on people’s radars. It wasn’t even until the late ‘80s that minicomics was a way to put yourself out there. You were invisible until an editor and a publisher, probably in New York gave you permission to be visible.

DB: So it was a geological variable then, basically. If you had the luck of geology with you… geography, sorry!

SM: Oh yes, geographically, yeah!

DB: That was a test. You passed, well done.

SM: It was just beginning to change, of course, because we had… Sim started Cerebus I think in ’77 was it? Thereabouts, a year or two later we had Elfquest, and I was watching those guys. So the idea of self-publishing was starting to look like an option, but I wasn’t as intrepid as they were. Then the independent publishers came along shortly thereafter, so by the time I got my job at DC, I had it in my head that, no, there’s this other way that I can go. I don’t necessarily have to go the traditional route.

DB: What was your first published work then?

SM: That was Zot! which started in 1984, and it was a pseudo superhero story, but it had a lot of other crazy stuff, kind of, folded into the mix. That one I did while working at DC. I was only at DC in production for a year and a half, but some things happened to my perspective, including my father dying, and I just somehow got it in my head that I should create something from scratch instead of trying to piece together a career from being given permission by publishers. So I just did it. I worked on the proposal while at DC and then I got four independent publishers interested and went with the one that could publish it sooner, just in case there was a nuclear war.

DB: You know, your reasoning is solid!

SM: I am not even joking. I was so convinced there would be a nuclear war before I could publish my first comic, and I just wanted my comic out there. I had this existential terror that my whole life will have been for nothing if I couldn’t at least publish my first comic.

DB: Do you still feel that terror?

SM: Well, no because nuclear war couldn’t possibly happen now.

DB: Well I should hope not!

SM: You know?

DB: Uhh…

SM: I’m sure we’ve eliminated that possibility.

DB: Yeah, I mean, disarmament worked!

SM: Have you ever heard that riddle, ‘what is the definition of the Soviet Union’?

DB: No.

SM: It is a nuclear arsenal that used to be a country.

DB: Huh.

SM: Doesn’t that fill you with…

DB: …dread. Yes. [laughs] Yes, dread. Yeah, I grew up with Chernobyl.

SM: Oh yeah.

DB: You did Understanding Comics in ’93 then. Was that straight off the back of finishing Zot! then?

SM: Yeah. As a matter of fact what happened was that I was determined to do Understanding Comics for a while, and I realised this was something I needed to do now, now, now, just as I began a long story arc in Zot!, and I couldn’t abandon it. I had to finish the series, but it took me a year and a half, maybe even two years to finish out that series. I just suddenly… it just hit me like an earthquake. I just realised, I have to do that book, and it was just torture waiting until I was done with Zot!. And the funny thing is that the stories I did for Zot! under duress, ones that I did towards the end of the series tend to be people’s favourites.

DB: Oh really?

SM: But inside I was just dying, because I really wanted to do Understanding Comics.

DB: So what was the impetus then for doing this, because Understanding Comics, I’m going to throw it out there and say that most people listening will probably have read it. That’s a fair assumption.

SM: I think maybe, yeah. That’s possible.

DB: It’s one of the first comics I read that took comics seriously, I think. It’s a very analytical way of thinking about comics, and it explains how to understand them. Where did this idea come from? Where did this drive, you know, this burning to desire to do it, where did that come from?

SM: Well, you’ve got to go back to that 15-year-old kid, who’s sitting in his friend’s playroom while his friend’s little brother is watching The Banana Splits or whatever and rocking back and forth, and looking at this Jim Steranko X-Men and thinking, ‘This art form has potential.’ You know, this was just the way my brain worked. I was always looking at it from a formalist point of view, even as a little kid. So that meant that with hanging out with Kurt or other friends, I was always babbling about this or that about how comics worked, about page compositions, about pacing, about techniques. I’d gotten really excited when I started to look at manga, and I saw that they had this different storytelling approach. I had a lot of ideas, and I was always trying to communicate them with people, but for the most part I was that guy at the party that, you know, you have to find the excuse to get away from.

DB: [laughs]

SM: You know, I think I’m a little OCD. I’m probably a little on the autism spectrum or something, and it was hard to take. I was describing visual things, trying to do it verbally and it just didn’t work. But I had a few examples out there of people who were doing nonfiction comics, like Larry Gonick and his Cartoon History of the Universe. I had examples of people who explain things, like certain professors in college, or James Burke and his BBC specials. There were examples of people out there who were just unravelling the mysteries of the universe, so I started to take notes for this idea of a comic about comics. For me it just seemed natural that it would be a comic.

DB: It’s the best format for it.

SM: Yeah, exactly.

DB: Say what you see.

SM: In fact, Will Eisner, who was very supportive of the book, his reaction was basically, sort of a forehead slap.

DB: Of course, because his book totally missed out on that, didn’t it?

SM: He could have done that. And he could have, he could have done it.

DB: Sure, yeah! That’s not up for debate.

SM: No, no. We know. I have this old… what do they call them? The little filing cabinet folders, the ones on the hooks with the little tab.

DB: They have a name and I can’t think of them.

SM: Whatever they’re called, hanging folders. They’re hanging folders. So, I’m keeping all my notes for this theoretical, ‘some day I’m going to do this book’ book, and I have dozens of projects at that point that I might do someday, including The Sculptor by the way, but this one is just weighing heavily on me. And it’s growing, and it’s growing, and it’s growing the folder until those little hooks are tearing off of the thing, because it’s gotten so heavy.

DB: Wow.

SM: Yeah, that was it. I just… I had to make it a book.

DB: That’s really interesting, that there’s this burning drive to do it. Because you did two subsequent, sort of, Understanding, Reinventing, Making Comics. The comics holy trinity.

SM: [laughs]

DB: Was there a similar burning passion to do those books as well?

SM: No. Actually, with Reinventing there was a real passion centred around the digital stuff, but it was also a little curdled, because when I did Reinventing Comics in 2000, I was talking about ideas, some of which had been kicking around in my head for five years or more. I was on about the infinite canvas and giving talks at MIT and such. I was doing that pretty quickly after Understanding Comics. I was obsessed with the web, but eventually I thought, ‘I’ve got to put this in a book.’ But that was more like, I felt I was almost late to the game.

DB: If your book takes however many months to go to print and then come back from print and then go to shops, the internet develops at a really… a pace quicker than publishing, I think is fair to say.

SM: Exactly. Yeah, and I was talking about things that were difficult to talk about in print. They were easy to demonstrate. Understanding Comics, anything I had to say I could demonstrate right there on the page. What I had to say in Reinventing was harder.

DB: Yeah, because you can’t click on the page itself.

SM: Exactly, yeah. Whereas Making Comics, I like Making, and I think Making is a more solid book, but also Making had the drive that I was trying to literally teach myself to be a better cartoonist. I knew I had this graphic novel coming up, and I knew it would help me as a student. Basically I was getting up on my own shoulders and then pulling myself up.

DB: [laughs] Yep, I understand how the physics of that work!

SM: Speaking of The Goon Show–

DB: Of course, yeah! Or pulling yourself through a telescope.

SM: [laughs] Yeah, yeah!

DB: I know my Goon Show. Going back to Finland and this meal we had in this restaurant. I remember someone asking you about… I can’t remember if it was micropayments or if it was about definitions of comics and things, and you were very calm and very reasonable, and the long and short of it was, ‘I don’t really want to talk about this.’

SM: [laughs]

DB: Do you get asked the same questions over and over and over again?

SM: Oh yeah, some.

DB: Is that one of those questions?

SM: Yeah! [laughs] The definition of comics, well, ‘What about single panel comics?’ or, you know, ‘They combine words and pictures and how about that?’ Those come up a fair amount, but it’s not… I don’t have that bad a cross to bear. Somebody who writes a popular superhero book probably gets more irritating common questions. And you know, these questions, they are interesting. ‘Where do you get your ideas?’ is the old whipping boy.

DB: I’ve got that one in the chamber. It’s ready to go. Just strap yourself in Scott, because we’re gonna [tongue click] pooow.

SM: We’ll get around to them.

DB: We will.

SM: Even the simplest question like that, probably, it has depth.

DB: You bet. I love that question.

SM: Yeah, and I don’t really mind so much. Also, sometimes the answer changes a little. I mean, certainty, ‘What’s the future of comics?’ does change, but it’s just a little bit too broad.

DB: [laughs]

SM: For a while it was hard to talk about things like the economic stuff like micropayments, which I got in a lot of hot water for in the early part of the century. It’s hard to talk about that without sounding defensive.

DB: How do you mean you got in hot water for it?

SM: First of all I lost the bid. I just figured, ‘You know, maybe I could just reinvent the entire world economy so that I could have a job in it,’ and this seemed like a reasonable idea.

DB: I mean, the best way to predict the future is to invent it after all, as Alan Kay said.

SM: I talked a lot about micropayments until the 10th or 11th startup that contacted me seemed like they had a good system. Couple of Stanford grads, they had something called BitPass, not to be confused with Bitcoin, though there are some vague connections there. They had a system I kind of liked. We gave it a try and we failed, and we failed spectacularly, because it was also very, very tied up with various feuds that I wound up an unwilling participant in with popular web cartoonists who felt like their model was being ignored, or whatever. The whole thing was just depressing. It was depressing. We tried, we failed, and I invested a lot of time in something that didn’t come to fruition. Now looking back on it, I realised that you really can’t accomplish anything significant over the course of a career without having some pretty spectacular failures. I think a lot of people who do manage to accomplish something significant usually look back with some pride on their failures, and I’m beginning to get a little closer to that point. But for one, it was hard to talk about it, because I didn’t… it’s hard for me to talk about something where I don’t have a specific positive agenda to offer. All I had was rehashing the past, and I’m not a person who enjoyed rehashing the past.

DB: No, that doesn’t sound fun. Sorry for drawing you into rehashing the past Scott. Sorry about that! So, where do you get your ideas?

SM: [laughs] What is it Neil says? Neil has the best answers. Neil Gaiman says that there’s a little shop. He gives the address, and there’s this lovely woman who will sell them to you for quite a reasonable price.

DB: [laughs]

SM: Actually Jillian… I think it might have been on your show, Jillian Tamaki said recently that like most of the artists she knows, and I’m included in this one, just say that is not the problem. The problem is finding the hours to execute the ideas you have, because… but if you’re going to take years to do a graphic novel, how many more ideas have you come up with while working on it?

DB: Yeah. If you have one idea per week, and you have 52 weeks in a year, and you have however long… you know, it gets silly after a while.

SM: Yeah, it’s insane. But I will say though, as a general philosophy of learning, I try to cast a very wide net. I get my ideas from everywhere, so I have a very voracious appetite for movies, for music, for TV, for life, for experiences and relationships and all, and it all goes into the same pot. And by having that wide net, I also have a wider data set from which to derive connections, and the connections that I see often, are the origins of those ideas.

DB: I completely agree. I think that ideas are where two things… I’m making gestures with my hands, like there are two spheres either side of my head. But you have these two things that somehow become connected, or they bump into each other, and that spark that comes between those two things is an idea. Then whatever you do with that spark is up to you of course. You can ignore it, you can write it down, you can turn it into a book, but for me ideas have always been about connections between things.

SM: Yeah, absolutely. Ideas have valences and they match up with other ideas in some unexpected ways, and you can create these new compounds that are genuinely new. I don’t subscribe to the notion that there are no new ideas. First of all, to posit that you have to logically posit that there was a time at which the new ideas had been exhausted.

DB: Yeah, we reached peak ideas.

SM: Exactly, that’s it! Congratulations Bob, that was the last new idea! Back in 1987, you know, 1976-

DB: You invented the car, and we’re done.

SM: Yes, of course you can look at any work of fiction or art and find parallels or precedence or elements of that work that in some way predate that work, of course. But no, there are… it’s new enough, some of the things. Even in the 20th century, maybe even the 21st century there are works or ideas that have come along that you can say are genuinely new, that have, as their beating heart, something that’s fresh and new in the world. New enough.

DB: Yeah, I think ideas have to have a strain of recognisable DNA for them to be accepted. Does that make sense?

SM: Yeah, although when Duchamp signed his name to a urinal, you could say that that was as clean a break with the past and had as little of what was previously understood to be any kind of artistic expression, as anything that had come before it. Maybe that was the last new idea, Dan. Maybe that’s it!

DB: Maybe it was.

SM: It was 1912, or whatever.

DB: Just draw a red line on the calendar at that point.

SM: Congratulations Marcel! [laughs]

DB: Congratulations, you’ve achieved so much.

SM: The last idea!

DB: [laughs] And it was an idea that just was waiting to happen as well. You know, it was one of those things that zooms around the universe just waiting for a fertile mind. Oh boy. You mentioned as well, we’re going to talk about The Sculptor, which is your book that is coming out imminently on February the 3rd?

SM: Yes, February 3rd. I’m trying to get better about saying that. Let it show we consult the talking point.

DB: Let’s!

SM: February 3rd, from First Second, the eminent publisher.

DB: First Second in the States, and SelfMadeHero in the UK, and this is a synchronised book launch.

SM: Yes, and also BAO Publishing in Italy and Planeta DeAgostini in Spain and Rue de Sèvres in France and Scratch in the Netherlands and I’m not sure of our Korean publisher. This is all within about a month of each other.

DB: Oh wow.

SM: Oh, and Germany is Carlsen.

DB: And you’re going to every single launch party on the same evening.

SM: We don’t have a Korean launch party, but I am actually going on a European tour, which will take me to all of those territories within a month or two of the book coming out.

DB: Wow.

SM: Yeah, and that’s after the American tour, which is, like, 15 cities in 16 days I think.

DB: You’re giving me a tight chest just thinking about it! It sounds great.

SM: It’s pretty nuts.

DB: Horrifying at the same time. Oh boy. So the book itself, I mean, you kind of alluded earlier that it’s an idea that you had a long time ago.

SM: Yeah. Well it goes back to my… just past adolescence almost. I had this notebook in… I think it was middle school or high school. I forgot when I got it, but it was one of these old three ring binders with that typical 1970’s denim cover. It was stuffed with ideas, and you can see all of these goofy ideas for superheroes that I had, like Thrombor, the Human Superball. Some day I’m going to do him. He was awesome.

DB: So everyone else, back off! That’s Scott’s.

SM: He was made of this material that was like flubber. It bounced with just a little more energy than the initial force, and he could just bounce around. I think that would be a great superhero. Anyway, so I had these goofy superhero ideas, and pretty soon thereafter I had this idea about somebody who could shape matter with his hands, but instead of fighting crime or whatever, he just made art. He was a sculptor. Okay, so that’s just… what is that? That’s just a silly power. This kind of thing that a kid comes up with, but then it mutated into this Faustian deal with death. Then soon after meeting Ivy, who I would marry many years later, but who I was secretly in love with for seven years, she became this love interest. Okay, now the story… okay, it has a few more elements. It’s still this big, corny piece of cheese, but there’s something in there. There’s some narrative interest in there. Then, as I came to understand how the story would play out, and just a few years after that, just out of college it clicked, and I realised this is actually a really good story. It’s still a big, corny story, but if done right it could be pretty amazing. So it just sat in the back of my head for years. Literally close to 30 years, I don’t know. It’s a very, very long time.

DB: So it incubated.

SM: Yeah, it incubated and what happened was that it was a young man’s story, but it was the old man who sat down and finally wrote it. I was almost twice the age when I sat down to write the thing, and with the help of Mark Siegel at First Second, who’s a really good editor, I think we brought the older man’s experience and perspective to it, and I really took the business of writing very seriously, and I discovered just how much more substantial the story was in the details, in the individual moments. Even if it seemed like this big, prog rock opera, you know? [laughs] In broad strokes, right?

DB: Because this is a long book.

SM: Yeah, it’s a long book. It’s almost 500 pages, but in the details it was something much, much more. And I was able to really discover for the first time what serious writing, and serious as in the hard working process of writing and rewriting and figuring out what you actually want to get across with a story, what that was like. It was terrific. I really enjoyed working on this.

DB: In terms of sitting with the same story for 30 years, I don’t know if I’m going to be able to ask this question properly, but because it’s an idea that’s lived with you for so long, was it difficult to tie it down into one final form? Because it’s lived in your head for so long as this, sort of, ethereal idea that I guess did change over time, did you become comfortable with the idea that it did change over time, and was it difficult to then nail it down into that one final, finished thing that’s now printed as an actual finished, final thing?

SM: Well, I wasn’t really wedded to much, except the skeleton of the story until things got serious. So I made a lot of changes in the process of writing it, but there wasn’t anything that I had been clinging to for 20 or 30 years that I had to let go. What I had, and one of the reasons why I continued to think this was a story worth telling, is because occasionally I would tell somebody the story. Just over the course of a minute or two, I would just describe the basic beats of the story, and even just standing in the supermarket with a friend, I would get an emotional reaction about the story. Because it was a good ending, the way the whole thing played out had… I don’t know, it had something. I could tell, this has something, but I hadn’t fleshed it out too much. One of the interesting things that happened, and this is a little like Understanding Comics, is just at the point where I realised it was time to begin work on this seriously, we started the tour for Making Comics, which means I couldn’t work on it.

DB: Ooh, forbidden fruit!

SM: Yeah, for an entire year, all I could do was think about it, and that’s what I did. I thought about it. I took notes, but for the most part I just sat there, Ivy did all the driving, because I’m not to be trusted behind the wheel.

DB: Worth noting.

SM: I sat in the passenger seat, staring out the window and just thinking about the story. And that was an amazing process, because what happened was, I was considering all the ramifications of the story, and making sure that all the planets were lined up correctly, and that the story proceeded in a way that was consistent and logical. That was good, I liked that.

DB: It’s not very often you get that time to just sit and think.

SM: Exactly. That was a great gift. Not only that, but the fact that frankly I had a good agent, who got me enough of an advance, that I was able to work on this thing for a long time. I also had an editor who saw where I was going with it, and at one point basically just told me, ‘Let’s just throw away the schedule, let’s get this right. Let’s just take the time.’ Both of us were very committed to taking as long as we needed to, to get the story right. Before I ever drew a single, finished panel, I had spent two years on the layouts. I did 500 pages in tight layouts. My layouts are very anal-retentive. They’re not particularly sketchy, they’re very tight. So I had basically drawn the entire book, and then I redid it, and redid it, and redid it. Four drafts of just tearing it up and putting it back together, until we were happy and felt that yes, this is the version that we like. Then I still, after I finished, took another three years to draw it. I still went back at the very end and redid the first 40, 50 pages.

DB: How long was this entire process then?

SM: It was five years altogether. I’m not counting the sitting in the car thinking about it.

DB: Or the previous years from that first…

SM: Yeah, right. The 20, 30 years before that, yeah.

DB: Wow. It’s good, I really enjoyed it! I told you before, and I haven’t quite finished it yet, but I’m hooked. As soon as I hang up, I’m going to finish it.

SM: We should say for the listeners that you only got it, what, like 20 hours ago, and it’s 500 pages.

DB: It’s a big, big book!

SM: It’s very thick.

DB: [laughs] But yeah, I’m hooked. I’m literally going to hang up and then finish reading it.

SM: Awesome.

DB: Yeah, really looking forward to it. You mentioned about this slow working of the story. Do you approach the story in a similarly analytical way that you approached the form of comics?

SM: No, because… well, I mean yes. I’m sorry. The correct answer is yes.

DB: [laughs]

SM: But not with the same spirit, because for years I was very much a formalist, and I accepted my role as, okay, I’m the mad professor. I’m tinkering away. I’m concocting new reading directions and compositions and playing with the form. This time, the important thing was to impersonate my opposite number, and to create something that felt intuitive, it felt natural. I was trying to follow that advice somebody once said, ‘You have to figure out what you want to say in a story, and then bury it.’ I was trying to bury the theorist, and harness my deeper instincts of what made the story right, to just know that it was right. But that didn’t mean that there wasn’t a lot of analysis in the editing, and there was. When I was rewriting and rewriting, I went for long walks without any music. I turned off my phone so I wasn’t listening to anything, just thinking about what needed to be done, where the story wasn’t working and why, and that was a very analytical process, but it was all in the service of transparency, of creating something that simply reads. Where you start reading, where wherever your eye lands, you’re on this conveyor belt and you can’t stop reading, because it’s just happening in front of you. That’s what we were looking for.

DB: It works. I feel like I’ve been yanked off this conveyor belt by having to talk to you.

SM: [laughs] Right!

DB: You swine! [laughs] You mentioned travel as well, your tours. You get invited to all sorts of places to give all sorts of talks. How do you fit all of that alongside what I imagine must be a fairly hectic drawing schedule?

SM: During those five years, it’s funny because I did still travel. I mean, while I was working on the book I did probably… oh I don’t know, about 60, 70 different trips. Some of them overseas, some of them quite long. Earlier this year I did two months at a Tennessee University, but the book was more or less done at that point. Not completely done, there was little mechanical stuff we were still tinkering with, and I did want to redraw those first 40, 50 pages.

DB: [laughs]

SM: Yeah, I get a lot of invitations. Now that the kids are grown, Ivy’s coming with me a lot. She’s been with me for almost this whole year, and that’s been terrific. We just got back from China, we did two weeks there, and Santiago, Chile. First time I’ve been in South America.

DB: Amazing.

SM: But yeah, I do lectures at universities, computer companies, festivals, and that’s also… I mean, presentation is an art form too, and it turned out to be something that I think I’m pretty good at.

DB: I would agree with that. I saw you give that talk in Helsinki and it’s a very slick show!

SM: [laughs] It is. I try to synchronise everything so that as I’m talking, images are just sliding up under my feet. It’s a challenge, it’s a creative challenge and it’s one I kind of took to. And I do it a lot now, and word gets around and I get invited to places, sometimes multiple times. I’ve been back to MIT, Stanford, NYU multiple times. And it helps support the comics, you know? It’s just another income stream. Two kids in college, [laughs]. I kind of have to say yet, basically.

DB: Yes please!

SM: The way I say it, I mean, it’s not that much of a cross to bear, because I mean, if the worst thing is, if I can’t only do what I love to do, going places and talking about what I love to do, it’s not so bad.

DB: That’s a pretty good second best.

SM: Yeah, exactly. It’s not bad at all.

DB: So you’ve got the promo tour for The Sculptor coming imminently.

SM: Yeah, February 3rd it all… bang, that day I begin that 15 cities in 16 days, and then I’m off to Europe right after that.

DB: So you’re going to be busy for, I guess, the whole of 2015 then.

SM: I think so. 2015 is going to be a lot of travelling, but I’m also working on the next book, up here, once again in my head.

DB: Staring out of the window.

SM: Right, but also in the talks in a way, because we’re doing a lot about what the next book is going to be about, is working its way into the talks. That’s about visual communication and visual education generally, which is the next frontier for me.

DB: Is this fiction or nonfiction?

SM: Nonfiction. I’m going to be doing a book, probably digital first this time. So we may be starting out with a tablet version. I want to do a book that deals with the common principles and common roots of different kinds of visual communication. Everything from information graphics, to educational animation and comics, to data visualisation. Even facial expressions and body language, and just see if I can distil what principles lie underneath all of these things, because I see people in different disciplines trying to reinvent the wheel, and I think that there are fundamental principles. I’ve been describing it as a kind of Elements of Style for visual communication. It’s something that I’ve been passionate about for a while.

DB: Do you think comics kind of, sets your brain up for thinking this way, or do you think that your brain set your comics up for thinking this way?

SM: A little of both. I mean, it’s true, it’s like that particular orientation probably affected the kind of comics I do. But I think cartoonists are maybe uniquely, if not qualified, uniquely…

DB: …practiced?

SM: Yeah. It’s a natural transition to think in terms of, ‘what results does this picture get?’ If you’re in the fine arts, it’s very hard… critiques are just murder for fine art students, because everybody just sits around trying to figure out, ‘God, is there anything I can say about this painting that won’t offend my friend over there who made it?’ But in comics you have very specific goals, you know? You hope that this image will trigger this reaction, this recognition. If you’ve drawn a face with an expression on it, you have a hope that a particular emotion will be evoked. If you draw a bicycle, you hope it will look like a bicycle. If you draw Toronto, you hope it won’t look like Seattle.

DB: Or Vancouver.

SM: Or Vancouver, all these other places with needle-y things on the skyline.

DB: Heaven forbid! [laughs]

SM: So, that means you can measure those goals, and you’re thinking in a very practical way. You are communicating with images. You’re trying to ring the bell, you’re trying to get a result, and that’s actually a lot of fun, because now we can look at whether or not you succeeded and talk about the solutions. From an educational standpoint, it’s fun to be a comics teacher, because there’s always something to talk about.

DB: But this is something that I talk about with my students a lot. When we’re trying to figure out a layout, when we’re trying to figure out a composition and something’s not working, I’ll make my students list off what it is they want to achieve. Like first of all, okay, so what does this need to do? What’s the bare minimum? So we list it off, and I’m like, ‘Right, okay. Now in your picture, solve those three problems that you’ve just posed for yourself there.’ And the process becomes far, far easier, because, like you said, you’ve got something to measure it by. You can be objective about it, and you can put as much heart as you want into the drawing. As a component in the story you can be analytical about these things, and not lose the heart, I guess, of the story. It’s a real multifaceted thing, drawing comics. It’s harder than it looks, isn’t it?

SM: And no matter how subtle the mission, no matter how nebulous the effect, the fact is, you’re still going to have this wonderful little gallery of short-term goals. Things that you want to get done, and that’s a gift. To be able to measure, to know, to wake up in the morning and know, ‘I am going to solve problems today.’

DB: Do the problems change over time? When you were saying that, I was thinking back to the problems that I had when I first… the very, very first comics I ever drew as a grown adult trying to make comics, not as a kid having fun with comics. I remember my problems were things like, I’d draw the speech bubble and then say, ‘How on earth do you fit all the words in there?’ They’d be all scrunched up around the edges. The problems I was trying to solve were incredibly practical, you know, just craft things. I know for me that the problems that I’m trying to solve now are, ‘How do I get this idea from my head, into the head of the person reading it.’ It’s like telepathy, they’re the problems that I’m trying to solve now.

SM: Well it is.

DB: It’s exactly what it is.

SM: You’re trying to evoke a mirror of your thoughts in others.

DB: It’s hard!

SM: Yeah, it is hard. And you can never do it completely, right? But that’s the burden of all artists, in all media, is to evoke that mirror. Yeah, it’s tough.

DB: You can’t stand next to the bookshelf in the bookstore and say, ‘Right, before you get started, a few things you need to know.’ You just can’t do that, physically can’t do that with every copy of the book.

SM: No, but that’s the human condition. I even wrote about that in Understanding, that notion, why do we have all these different forms of storytelling media, other media? It’s because we can’t communicate directly mind to mind, and that’s the burden of being human. So we’re trying to overcome that burden, you know? Actually, going back to Understanding Comics, what you’re describing in a lot of ways, is the progression from surface to core, and yeah, I think most of us start out with the surface. First thing we do is try to get that really cool shine on things, or whatever.

DB: Get the hatching, really, really detailed.

SM: ‘I can do that, I can make lines like that.’ Then pretty soon it’s like, ‘Ah, but I can’t get the hand to look like a hand.’ And okay, now it’s craft, right. Then eventually you get down to the structure of the page, and all you’re doing is you’re moving from the skin down to the core.

DB: Do you think there’s anything beyond the core?

SM: [laughs]

DB: Are there layers we haven’t peeled away yet?

SM: Yeah, actually yeah, there is because what happens is, you think you’ve come down to the middle of it all, and you realise you’ve been asking the wrong questions. But then you do get down to the, ‘Why do I make this? What’s the purpose for this?’ You have to get to the fundamental stuff. Why am I making art at all? Why do I care? What do I hope to achieve? Is it really that important that anyone remember me after I’m dead and gone, and is that even a realistic hope? No matter who I am, doesn’t everybody get forgotten? How do I want to spend my minutes, you know?

DB: Exactly. Well that’s as good a note to end upon as any! [laughs] So from February the 3rd people can buy The Sculptor, across the planet, by the sounds of it, on the day of release. Where’s the best place to find out more about you? You have a website and a Twitter.

SM: Yeah, just scottmccloud.com and I even have… the last blog post before today’s was me just plunking the book in front of you, and turning it around and showing you what it looks like. The hardcover comes out first. It has a neat little dust jacket, and stuff underneath. By the time this airs you may have to dig through a few more blog posts to get back to it. And I’ll have a page on the site just devoted to The Sculptor pretty soon.

DB: Excellent. And the Twitter?

SM: Twitter, I’m just @scottmccloud. Just all one word, all smushed together, lowercase.

DB: Lovely. Well I hope next year goes really, really well for you. Well actually, by the time this airs, this year. I’ll be honest, I hope 2016 goes really well for you as well. I’ll put that out there.

SM: [laughs] I hope it goes well for both of us!

DB: Thanks very much for speaking to me.

SM: Thank you Dan.