Ryan Cecil Smith and Dan Berry talk about finding your voice, drawing with purpose, self publishing, risograph and how nobody cares about your stupid brush line!

Check out this episode! If you want to help support the show (financially) sign up to the Patreon campaign to donate a dollar or two per episode, if you want to support (morally) then tweet about the show and rate and review it on iTunes!

Transcript by Renée Goulet;

Dan Berry: This is Make It Then Tell Everybody. I’m Dan Berry. Ryan Cecil Smith sat down to talk with me about finding his voice, drawing with purpose, self publishing, risograph and how nobody cares about your stupid brush line. This is Make It Then Tell Everybody. Hey look, it’s Ryan Cecil Smith! Hello.

Ryan Cecil Smith: Hey.

DB: How are you doing?

RCS: Good.

DB: Excellent. Can you describe for us where you are at the moment?

RCS: Sure, I’m in my apartment. I’m in my bedroom in Osaka. I live in Osaka, Japan. I live in a nice little quiet neighbourhood, not too far from the centre of the city, so it’s real easy for me to go downtown, but around here it’s real calm.

DB: My Japanese geography is terrible, so whereabouts on the map of Japan is that?

RCS: Osaka is south of Tokyo. Tokyo’s the main big city of course, and I often tell people that Osaka is a good place to spend more time in, because it’s right next to several other big cities like Kyoto and Nara, which are beautiful, traditional places. Osaka’s a big city, it’s in the south, it’s a little bit warmer, real reasonable weather.

DB: It sounds really nice. Congratulations on all your successes. So you’re a cartoonist?

RCS: Yes, I am.

DB: A genuine, proper, make money doing cartoons, cartoonist.

RCS: I make cartoons all the time, and that mostly means comics, and I do it, sort of, like, full time-ish, like, I spend a lot of time on it, and it’s buoyed by illustration jobs or other freelance jobs. So, kind of half-ish.

DB: Okay. It’s all drawing through?

RCS: Yes, it’s all drawing, thank goodness.

DB: When did you start drawing with any real purpose?

RCS: I figured out that I wanted to be an artist when I was in high school. I went to an art school, I went to an art college and I majored in printmaking and I did a lot of drawing there. I always really cared about comics, but if you say ‘drawing with a purpose’, I mean, I would say that I don’t know if I have anything worthwhile to say now, or how much of a voice I have, but I didn’t feel like I had any voice or any sort of purpose with my work until I was in Japan. Then I started thinking about how to make work and enjoy myself. I would say that’s when it became a bit more purposeful.

DB: This is something I’m always really interested in, because when people say that they went to art school, I mean, it’s weird to think that you went to art school but you didn’t really have this sense of purpose. I sometimes feel that when people go to art school they get carried along by the system, you know? They excel at art in some way, and so then they do art here. Was that your experience, of being carried along by this system, or was it a more definite choice? ‘I want to be an artist, therefore I’m going to art school.’

RCS: Well in my case I definitely wanted to be an artist, and I think I was ambitious within the course that I took, mostly, or within the curriculum I took. I’d say I worked pretty hard at the course that I cared about. Printmaking after all, is kind of a labour intensive thing, so you know, there are a lot of cases where I might put a lot of time in, and I would think about the work a lot, so no. I mean, I definitely wanted to be an artist 100%. I knew I was going to be, but I would just say that I didn’t really… I kind of want to say I don’t think my work was… I’m not saying it wasn’t good, but I didn’t have a voice until I got out. Looking back at that work, I don’t know what to think about it.

DB: When you say ‘a voice’, what does that mean? Because I know what you mean, but I think that people out there listening might not quite understand.

RCS: This is just how I talk about myself and how I think about my work, and the way I think about other people’s stuff, but I think it’s really important when you’re starting, you see what artists you like and you look at their work and you hear what they talk about, and you hear what’s important to them and how they are. You, sort of, take those into yourself. Like, I don’t know, for example I would read interviews with Chris Ware and the stuff he’s into, and I’d be like, ‘Oh yeah, I like that stuff,’ you know? I’m not saying I didn’t like it, or that was fake, but I don’t know. As I got older I could approach things with… maybe for me, finding a voice was clearing out thing that weren’t 100% I cared about making work about. The work that I was doing was, ‘Yeah, I’m into this in this way, and I know why I like it, and I know why I’m approaching it this way.’ It’s not to denigrate any of this stuff, but paring down a little bit, what I do and what I like.

DB: It’s kind of like filling your head up, full of stuff when you’re young, and then finding your voice is taking out the stuff that doesn’t speak to you as much.

RCS: Yes, yes. Because I don’t know how you could not fill yourself up with all that stuff. That’s super important, but it’s like, if you don’t build something out of that, then you’re really boring. You know what I mean?

DB: Oh sure. I think one of the biggest crimes in comics is comics that are just drawing, that don’t have anything to say. They don’t bring anything new to the table, and they don’t tell you anything. I think that’s a crime.

RCS: Yeah, that sounds like a crime.

DB: Punishable by banishment from the world of comics.

RCS: Whatever way someone wants to do work is cool, you know, but it’s like…

DB: Yeah! [laughs] I’m being petty.

RCS: Oh, okay. Yeah. I mean, it just depends on if it’s really interesting, you know? Interesting just means like, are they actually interested in it in a way that I’m actually interested in it, and can I understand that and share it? If I’m digging that, that’s a thing, but sometimes you look at stuff and it’s like, ‘This is boring.’ So, it’s okay, it’s not bad. It’s just personal too, so you have your personal taste.

DB: Yeah, it’s not a crime. I take it back.

RCS: Thanks.

DB: [laughs] You win this round! You win!

RCS: I don’t mean to, but…

DB: I am keeping score here on the scorecard. The Make It Then Tell Everybody scorecard. So you mentioned that you didn’t really find your voice until you came to Japan. So was going to Japan part of finding your voice, or is that a coincidence do you think?

RCS: Well, it kind of pushed me off my axis, you know? So I was forced… I mean, I couldn’t rely on the same lifestyle and the same… I don’t know, it was just something totally different, so it made me engage with the world around me. I don’t mean that the way I engaged it changed, although it did.

DB: But it pushed you out of your comfort zone.

RCS: Yeah. That’s right. Well said! I pushed me out of my comfort zone, that’s the answer.

DB: Hey, there we go! I’ll edit it so that you said that rather than me.

RCS: Thank you.

DB: [laughs]

RCS: Yeah, that’s what I mean. It was just a different thing, so I was just like, thinking about stuff differently.

DB: How did you come to move to Japan then?

RCS: I applied for this teaching job in Japan through something that’s called the JET Programme, which is basically like a programme that’s put together by the Japanese government. You actually apply for the job at Japanese Embassies around the world. What it is, it’s hooked into the public school system to most of all the prefectures, most of all the states in Japan. Basically you apply through the Embassy, you base your application on your teaching and cultural experiences, and maybe your experience with Japanese culture, but I was actually a weird candidate because I didn’t have a lot of history with Japanese. I had a bit of teaching experience, and I had a few teaching experiences and travelled a bit, and that was proof that I could go into a new environment. I just want to say I’m bollocksing this answer, and I’m trying to think of how to put this.

DB: No, you’re doing fine. Don’t worry.

RCS: Basically I applied at an Embassy. It was a real long shot job, and also for me, when I heard about this programme, I thought that it was for people who were big Japanophiles. So I thought, ‘No way is that for me.’ I knew a guy who applied for it, and he was like, you know, always studying Japanese all the time, and I was like, ‘Okay, that’s not for me.’ But then they came to my school and gave a little presentation, and I was like, ‘Oh man.’ They don’t want people who are only super into Japan, they wanted people with all different interests, who could handle the job. The job is, it’s a teaching job, but it’s also a cultural exchange job. It’s as much like cultural ambassadorship as it is teaching. I’d say half of my effort is on that kind of thing, more than it is just teaching. So anyway, I applied and I was a wait list candidate, but I got it at the very end. So I came over here and it was a good thing. If I hadn’t done that job, I knew that I was just… I had a fine arts degree, so I knew that I wasn’t going to make money from the artwork I did. Which, by the way, is a kind of weird assumption to come out of school with, but that’s what I had. I don’t know, I kind of think that was dumb, but that’s how I felt. I felt like, ‘I’m just going to get a job somewhere, so I might as well go somewhere interesting.’

So I was actually looking at places in the US. I was thinking about going to Chicago or Portland, and this Japan thing. I actually bought a ticket to go to Barcelona and to go there after school and see… I didn’t really have a lot of plans, but I just wanted to get out somewhere. Then near the last minute I got the job in Japan, so I threw those tickets away and went to Japan instead, because it was a safer bet. I mean, it was farther away, I didn’t know the language, I didn’t know… I knew very little about Japan. Embarrassingly little. But there was a steady job there, and there was a network of people in the programme to support me in whatever way that would be, I didn’t know. So, it was the safer bet, and it turned out good.

DB: You took up to go teach in Japan, how did you… you know, taking your comics. I mean, were you doing comics at that point already, and how did that translate across to Japan? Do you see yourself embedded as a cartoonist in Japan or… I don’t know if this is going to sound strange, or do you see yourself as a cartoonist whose domicile is the internet?

RCS: Oh, that’s a good question. Well, I think of myself as a cartoonist who’s embedded in Japan. I don’t think of my domicile as the Internet, but I mean, I made comics before I went there. I mean, that’s what I was big into in school, and even before school, and I’d self published and stuff, and I’d been to SPX a few times in college. I felt like, yeah, I am a cartoonist. But when I got to Japan I didn’t have a computer for putting books together, in that normal way you put books together on a computer, and I didn’t have any printing stuff, so I wasn’t sure how I’d make the books, which is how I always did it. I always did self publishing and stuff, but it turned out that I found those things, and it actually led me to do a lot of work… I mean, this is why I’m not an internet person, or why I responded in the negative to that, is because when I got here, I was like, ‘Oh, I don’t have any computer, so I’ll just do everything by hand.’ So I did a couple books entirely by hand, the whole process. My first few books here, I did of course all the drawing by hand, and with white out, and then I would make one photocopy to iron the blacks down, make it all black and white, and then I would apply finishing touches with white out and black, and then that’s what I would cut up and put as printer spread and put that on the print bed. So super analogue. That was a cool way to break process in a new way.

DB: Now I often think there’s a split between working traditionally with your hands, you know, inky fingers, getting stuff down on paper and working on a screen. I find it really, really difficult to draw onto the Cintiq or whatever. I find it much more tactile to work on paper. Is it a similar thing with working for a book that you’ve made, versus a website that has just scans of things on?

RCS: I get a lot of pleasure out of thinking about the experience of getting something, and finding it, and reading it. I’m not saying it about the smell of the paper or anything, but…

DB: But it is.

RCS: Well, but I feel like with a book, I know what it is, but if I put something online, what’s it going to be, some 1,000 DPI JPG that’s going to be viewed in a new tab, or in a new thing. So I don’t know, that was just a weird thing. I’m not saying that’s bad, but I’m saying with a book I get excited because, yeah, it’s going to be exactly this. It’ll be cool.

DB: When we were arranging this, I’m going to give the audience an exhilarating glimpse behind the magician’s cloth here. You wanted to send me the books physically rather than as PDFs, and you waited for the books to actually turn up before you sent me the PDFs. I think that was exactly the right idea. I mean, I want the listeners to listen to this: [rustling paper].

RCS: I can hear that.

DB: Yeah, it sounds pretty good. It’s got nice binding, and it’s got spot metallic, and it uses nice paper. And you’re right, this is a way more tactile, pleasurable sensory experience than just tapping away at my cold, emotionless laptop.

RCS: Yeah. I think people are excited to read books like that. I think it’s cool.

DB: I am!

RCS: But of course the audience is limited too. You know, there are trade offs.

DB: I mean, you print, let’s say 1,000 of these books. Does that necessarily mean that roughly 1,000 people will get to see it, and I understand that the audience online is way, way bigger, but you can make more money I think, from an actual book.

RCS: I don’t know Dan, I don’t know.

DB: [laughs] I said that with a raised eyebrow.

RCS: I don’t know. I’m not sure how much money you can make from a real book. I’m not sure how much money you can make from an internet book.

DB: Well this is the thing.

RCS: You should get one of those people who do, like, Patreon or especially I’m interested in those Storenvy books. Everyone’s different, but to hear how they feel they compare, because I’ve never done a Storenvy PDF thing. That’s the website where it’s like, you pay $2 for a PDF, Storenvy. I think I should do it really. I want to do it, it’s just like, when am I going to get around to doing that? I should do that, by the way.

DB: [laughs] Well this is interesting.

RCS: Yeah, I wonder how that works.

DB: I do feel that at the moment we’re in a transition phase from everyone giving everything away online for free, all the time, into a way of making online stuff pay. I think it’s difficult because everyone’s default setting when thinking about the internet is ‘everything’s free’. You know, you can download all of Game of Thrones for free if you know where to look, and you can do pretty much anything for free, if you know how to ask Dr Google. I think that we’re in this weird transition stage now for people finding out how to make money digitally, and how to make it pay rather than just giving it away.

RCS: I think one thing also is, I have a really enjoyable connection to people who buy my books, and I send it to them in the mail. I mean, this is such small fry stuff, but I guess it is pretty cool that I know people who tend to buy my books when they come out. Like, I know which names that I’ll expect to see in my PayPal orders. I feel so much more of a personal connection to those people than if it was just web orders. I think it’s real. I mean and… I want to say recently, sorry guys, I’ve been so overwhelmed I haven’t been very good about writing you little notes in the packages and stuff. I’m real sorry, but I’m trying to do better. But it’s a real thing! It’s like, I try to make the package nice and stuff. Nobody expects a lot, you know, but it’s nice that I send packages to people, that’s cool.

DB: When your parcels arrived through my front door, they were a delight to see even before I’d opened them.

RCS: Thanks man.

DB: That’s a throbbing endorsement there. People should go and buy your work.

RCS: I’m just saying I like doing that, that’s really fun, and I think people like getting it. I think people like buying it and like getting that way, and it’s more pleasurable and it’s more exciting than online. It’s not about saying that digital’s not the right way to make money, because we’re saying, ‘How do people make money?’ I talk to a lot of print cartoonists or self publishers and some of us, this would be at SPX last year, and people talk about, ‘Yeah, I don’t know which way’s the right way to go.’ It’s kind of a mystery. Nobody’s sure how much to give away for free or not. There’s no right answer I guess.

DB: Even when you’re working on something. I’m working on something at the moment that hasn’t been announced and no one’s seen, and I am desperate to share little photographs of work in progress and put things online, and I’m not doing it because I want it to be a bang, not a slithering whimper.

RCS: Yeah, that’s weird man.

DB: What do I mean by that! You know what I mean? I don’t mean slithering whimper, that sounds like I’m being really dismissive of anyone that puts anything online, and I don’t mean that at all.

RCS: I do that a lot on Instagram. I try to share as much process as I can on Instagram without putting spoilers into a book. That’s just shunted off towards like, people look at this on their phones. It’s not like a website, it’s not like a Tumblr post. I know, I like to share too, a lot. It feels good.

DB: It’s nice to have a little bit of validity come form it. You put something online and it gets a bunch of little likes, and you’re like, ‘Yes, I’m doing a good job.’ For me it feels strange not to have that. Not to be showing people things and not to have that little, ‘You’ve done a good job Dan, well done.’

RCS: It feels weird when I do most of my freelance work when I don’t share anything on the way, or very little, because I don’t want to make someone feel mad. You know, like I shared a little bit of a drawing and they’re like, ‘You’re not supposed to share that.’ I don’t want to get that, so I do tiny bits sometimes, but it feels weird to go through the whole process and not share anything, but that’s the right way to do it. One should do that, I suppose. I guess.

DB: I guess that I’ve just realised that all I’m looking for a lot of the time is just a slap on the back and an ‘attaboy’. Well done, attaboy!’

RCS: Yeah, but also it doesn’t feel… of course I know what you mean man. Tumblr and Instagram likes and faves and stuff, that’s a real endorphin shot, but also I feel so weird when I do a project and I don’t tell anybody beforehand. Especially for another publisher or for a client, because it almost doesn’t exist to me. It’s like, I do it, I make it, it’s gone. I don’t feel personally engaged as much, so it’s weird to not share it. It’s a weird experience.

DB: That makes sense to me. I guess because the work’s for someone else, it’s not your work.

RCS: Even just like, somebody else is going to do all the finishing, so I’m not part of that so I have to step back. You know, they’re doing their thing. So I don’t know, it just feels weird. It feels different.

DB: So a question that will arise from that then, if you feel that way, do you think that to be an effective self publisher you’ve got to be kind of a control freak?

RCS: I mean, everybody’s different, but probably you are.

DB: [laughs] That was a very diplomatic way of answering.

RCS: Yeah, I don’t know if I’m a control freak per se, but I care a lot about… I sweat the details. I don’t know.

DB: I am. I’m a control freak.

RCS: Look at Mickey Z’s comics. Those comics look wild and crazy, but you know she sweats the details. You know she thinks about… you know? But I don’t know if I would call myself a control freak like that, but I’m pretty hard to work with, I think sometimes, a little bit.

DB: I think I am, yeah.

RCS: When I’m publishing something, because you’re like the boss of a project that is basically you. It’s only you. But then if anybody else comes in, you know, I’m like…

DB: They might stink up this project!

RCS: ‘What do you mean you can’t do it in exactly the way I had envisioned!’ It’s so stupid.

DB: ‘I specified this Pantone! Not just red!’

RCS: I can just get kind of pissy, just stupid.

DB: No, it’s a necessary evil. Not necessarily that it’s evil though.

RCS: No, I think it is an necessary evil.

DB: Evil. Is evil the right word?

RCS: Yeah, you have to be kind of lame when you’re planning something. No, you don’t have to I guess. Like I said, you don’t have to be that way.

DB: I just choose to be that way.

RCS: I can’t help it.

DB: [laughs] So, where do you start with when you jump into a project then? I guess my main question here is, where do you get your ideas?

RCS: Ah yes, this question, which you ask on your podcast.

DB: I love it.

RCS: Well, I thought the first way you were asking it is a little different, but I’ll answer ‘how do you get your ideas’ first.

DB: See, I bailed on the smart question and just went for the dumb one.

RCS: Yeah, and you just jumped right into that one, but it’s cool. Whenever I hear you ask that on your podcast, because I’m a fan, is, I always thing… the first podcast I heard you ask about it was with Dustin Martz and… I just said Dustin Martz! Dustin Harbin and John Martz.

DB: Justin Martzbin!

RCS: Yeah, Justin Martzbin. That was funny, you combine everyone’s names in the interview.

DB: I had emails from people saying, ‘I can’t find this guy. Who is he? I can’t find his website.’

RCS: That was funny. Well that’s the first thing that I listened to from you, and I remember you guys going over that a bit, and for me it’s such a simple thing. I have ideas all the time. Where do you get your ideas from is like, it’s real easy actually. Honestly, I see stuff and I’m like, ‘I want to do something like that. How can I do it in a different way?’ And a different way is like some way that I’ll think of. So I’ll be like, ‘Oh, I love this, that’s so cool. I wanna do it, like, this kind of way.’ You know, my spin on something else, or take two ideas and mix them. I love this, and I love this. I could do these two things, or, this is funny, a lot of my ideas… this is so stupid. This is crazy. A lot of the projects I’ve started happened because of some ridiculous, small, physical thing in the world. I did a book because I had a few extra reams of paper, and I was like, ‘Oh, I have paper at this size. I should make a book for it.’ Just a small idea, but it turned into this big project, which makes no sense. Why should I do it that way, but I do, and it makes something cool. It’s a cool thing. You can feel it in the end product, like, ‘Yeah, this is cool.’ I’m working on a book right now, I found this interesting way to print something. I don’t want to spoil my thing I’m working on but, basically it was like, ‘Oh, I wonder how this would look? Well, if I’m going to do this I might as well do eight pages. And if I’m going to do eight pages…’

DB: You may as well do 16.

RCS: Yeah, like that.

DB: I may as well do 32 if I’m going to do 16!

RCS: Yeah, so I’ll do something dumb like that, but it’s a really fun way to approach making work. It’s like, I want to do this thing, I’ll make this thing, the idea’s there and you just develop it. And if it looks good to keep going, then it’s like, ‘Yeah, I’ll do it. It’ll be cool!’ It’s kind of weird, it’s arbitrary but it works.

DB: I’ve just realised that the question ‘where do you get your ideas from’, is basically the same question as ‘where does sweat come from’. Where does sweat come from? I don’t know, it just happens. Like, oh I exercised really hard and then it was there. It’s basically the same question and the same answer. It just happens, I don’t know how it happens, but now I’m covered in sweat, I need a shower. Or, I went to the gym and I had this idea, I was going to make it happen.

RCS: I feel like, you know, I hear that question made fun of in a way by people.

DB: Oh all the time, yeah.

RCS: But I think it’s made fun of by people who…

DB: …no ideas.

RCS: People who do talks or teachers. Teachers talk about this question, because you know, I went to an artist talk with Charles Burns. It was the first question someone asked him, so I see that it’s a big question. Don’t get mad at me, I’m not trying to be condescending, but what I say, it might sound condescending.

DB: No, please condescend me.

RCS: I’m working out the idea verbally, but I think someone who asks that isn’t really asking… like, if someone’s impulse is to ask, ‘Where do you get your ideas?’ I think it’s just because they don’t have anything better to ask, you know? I don’t think they really are asking that question, because I don’t know why someone asks that, ‘where do you get your ideas’, that’s an empty… it’s like just conversation.

DB: I think it comes back to what you were talking about earlier, with finding this idea of a voice, and I think that sometimes you get the idea that people ask that question because they haven’t found that voice of their own yet. So they’re asking someone that has, ‘How did you find that thing that you do?’ Which translates, because they haven’t found their voice, into, ‘Where do you get your ideas from?’ because it’s that physical thing you can see. We know that that physical thing you can see comes from understanding of what you want to say, and I think that when you don’t understand what you want to say, it’s all surface, so therefore what they’re actually asking is, ‘What are the steps that you took to be able to do what you do?’ which I guess is the more complicated version of it.

RCS: And that’s an interesting question to answer, yeah, but ‘where do you get your ideas from’, I don’t know how someone answers that. It’s just like, ‘I have them all the time.’

DB: You’ve got to be open to them. You’ve got to know that they’re out there, and if you go looking for them you’ll find them. I think so. So you’ve had this idea, you’ve taken these two things that have bumped into each other and they’ve had a little idea baby. What do you do with that? How do you capture that idea? For me, if I don’t write it down immediately it’ll dribble out of my nose and my ears while I sleep, and then it’s gone forever.

RCS: Well, it usually gets worked out in… I feel like my most fertile ground is in the first four pages of sketchbook stuff, where I’ll do thumbnails and writing out little bits of dialogue on a page. Usually it’s those very first pages where I’m really mining all the best aspects of this. Like, it’s going to be like this, like this. Kind of doing thumbnails or making notes about how things could tie together. Those original four sketchbook pages, or, you know, often two, just one open book, I’ll often go back to that spot to check for things, especially later in the project, to remind myself of what was it that this is all originally based in. What was the spark that got me really hot for the idea? Because later, you’re in the woods per se, but you can always go back and look at that and be like, ‘Yeah, right. Duh.’ That’s the thing, you know?

DB: This is the thing that got me pregnant.

RCS: Yeah. I was using a fire metaphor, not…

DB: Sure, I know. I changed it for you. [laughs]

RCS: Yeah, I’ll go back to that and I’ll make a bunch of notes and basically if I’m able to flesh out the whole concept pretty well in that small amount of time, like, feels right, then it’s start pencilling pages more roughly and seeing that it really is real, and then make a book. Start figuring out how much it will cost and stuff.

DB: Which for you is the difficult part of the process then? From having the idea all the way to packing up a box full of books and sending them away somewhere?

RCS: I think the difficult part is when you start to get lost from the original idea. Meaning it’s like, in the middle of the work of drawing it, especially, honestly, I kind of write as I draw. I think if you’re just doing scripts and then drawing that, I bet it’s more complicated for someone’s who’s in the middle of writing it maybe. But for me, when I’m halfway through a book or just a comic, whatever, it’s like, I have to remind myself of what got me into this and get back into that energy. Because the further I get from that original spark energy, it becomes more of a cerebral exercise where I’m making stuff. So that’s heavy and slower. It’s harder for me when I’m drawing pages and I’m like, ‘Wait, what is this supposed to be?’ I can almost get into a routine that’s a little boring, or I just am not remembering exactly the enthusiasm when I’m more than halfway into a project. I have to remind myself of that.

DB: That’s interesting, because I think it’s different from what I do. It’s almost the same, but the other way around, in that I’ll have that spark and I’ll try and capture that on paper, this is what I want this story to be about. I’ll do everything in thumbnail first to make sure that it works and my thumbnails are a couple of inches high and a couple of inches wide.

RCS: Same, I think we are.

DB: [laughs] Same, I think we are! That’s where I do all the heavy lifting. This is where I put in all of the brain power, and then the rest of actually drawing it, I don’t find it hard work, I just find it a lot of work, and I’ve realised recently that lots of work and hard work aren’t the same thing.

RCS: Yeah, it’s true.

DB: Realising that, oh, this is a lot of work, but it’s not particularly hard. I can pick it up and put it down. I can do a page at a time, or a panel at a time, and there’s just a lot of it. But the hard work I find, is that trying to figure out what this story is and how it works.

RCS: For me it’s the same thing at a different time, because what I do is like, once I get pretty far into it, and I’m kind of writing a bit as I’m drawing, it’s those story decisions, where it’s like, what should be happening in a story?

DB: How should this make sense, yeah.

RCS: It’s like the ‘how’ that I’m trying to figure out. I basically know the ‘what’, what it is and stuff, but how it’s supposed to work really. I put those decisions off for later, which is really fruitful I think, but it can also be frustrating to step back into thinking mode.

DB: Yeah. I try and do, because I don’t get an awful lot of time to do everything, I try and segment everything into sections. If I do all my heavy lifting thinking part at the beginning, and then sometimes while I’m drawing it I second guess my own decisions and think, ‘I should have done this, I should have done that,’ but I’ve set myself a rule. Like, ‘No, Dan from two weeks ago was right to have that decision,’ and just go with it.

RCS: That’s great man, totally.

DB: It’s like it’s someone else’s fault. You know, this guy who wrote this junk is at fault here, not me, the guy who’s drawing it.

RCS: Yeah man, that’s awesome. Sometimes I’ll be a little bit dissatisfied with how something came out, especially when I print something and I’m like, ‘Oh, I didn’t expect this to be this way,’ but on the other hand it’s like, what are you going to do, go back over that a million times? Just let it be a thing. It’s part of the history of the thing, it’s cool.

DB: Yeah, you’ve got to let it go sometimes. It’s never going to be perfect.

RCS: And also, you’re your worst critic, right?

DB: [laughs] I would hope that I’m my worst critic, because I don’t want to see anyone else do this kind of thing to me.

RCS: I think in a lot of cases there are things in your work where you’re like, ‘Oh, I wish this was different,’ but everyone’s going to be pleased with what you made. People who read your work are going to be totally into it. They’re going to be cool with it.

DB: Yeah, I think so. Okay, so you’ve got this idea and you mentioned that you do small thumbnails as well. How many times do you go through the process of refining the rough work before you get to the final work?

RCS: Good question. I would say that I tend to draw something, probably the finished drawing is the fourth version of something. So for a given page, you know, I did it in a thumbnail, and then I did a slightly bigger thumbnail. My first thumbnail’s going to be pretty small, a couple inches for a page, really small. But then I’ll try to lay out, maybe on half a sheet of paper or maybe four to a page, how the page is going to look. Then I will do a full page pencil, but you know, just the way it ends up working, I often end up drawing that twice, because just drawing the thing at the size it’s going to be, I just realise in doing it, ‘Oh, it should be this way.’ So then, basically I end up drawing it twice, and then I ink it. Usually for me, if I’m making storytelling decision while I’m inking, meaning like, it make a difference as to whether this thing is here or here. Where this person is standing on the left or the right. If I’m figuring that out on the inking stage, I’m probably going to mess it up. Like, it doesn’t work well. For me it’s a lot better to get it figured out in the pencils, because when I’m inking it’s really risky. I might do it weird. Because what I’ll do is I’ll think, ‘Oh, he should be standing here,’ but then I screw up the composition, the flow. The flow that was so clear in the thumbnailing stage, you know? It was so clear, but then if I start screwing stuff around later it’s weird, so I don’t like to make those decisions when I’m inking. I like the inking stage to be… it should be figured out. So that is the fifth time a certain thing has been drawn, from tiny to big, which is kind of a lot, but it’s alright.

DB: The inking then, is that relatively straightforward and fairly easy for you now?

RCS: I try to make it easy on myself. Like, what you just said about when you look at it as something someone else did. I think the inker’s doing his best, but if the inker doesn’t make every line look awesome, you know, if everybody else is doing their good job, 90% of the time and the inker is a little weird, it’s cool. So I try not to give myself too much stress about it.

DB: I used to beat myself up about that a lot. You know, ‘This final artwork here must be perfect. It must be as good as it can possibly be,’ so I’d redraw everything.

RCS: I think that’s more about the mind set than it is about the product, and I think that mind set is not good. When I was in college I lived with this guy, with my friend Lane Milburn. He just had a book come out called Twelve Gems from Fantagraphics, and man, Lane is such a great drawer. He is so good. He went to school, he started as a painting major and was doing Caravaggio style paintings. He’s one of those type of artists. So talented, right. Then when he would do comics he would just draw them off so fast. He would do these crazy looking monsters, and he would just draw it fast. He would just draw it, whereas I thought, like this is so stupid. I was watching too many documentaries with Daniel Clowes talking about drawing the perfect brush line. I’d be thinking about that stupid thing, and that is so dumb! You know, nobody cares about your stupid brush line!

DB: [laughs]

RCS: It’s that mind set of ‘I should make this perfect’, where actually, honestly, if you’re drawing honestly, if you’re drawing the way you draw, that is perfect. So that’s why inking, I try to treat it as kind of a dumb thing, and just let it do good.

DB: Yeah, let it live.

RCS: It’s not about some weird, perfect thing.

DB: Yeah. So you’ve got these pages, they’re inked, you don’t care about your… I’m going to use your words here, your ‘stupid brush line’. It’s all done. What happens next then?

RCS: After that I’ll scan them and I will put them into Photoshop. I draw with cyan coloured pencils, which is a really nice thing. This is an unexpected technical detail to talk about.

DB: No, I love this stuff.

RCS: I draw with a great cyan pencil, because what’s great about it is that I don’t have to erase them when I’m done, because the scanner scans in RGB, and then you convert it into CMYK, which is a thing in Photoshop, and then you just go into the cyan channel in Photoshop and delete the cyan. So all my pencil lines are just gone, like that, and my inks, as long as I’m not inking too, too crazy light, they’re all fine. So that’s why I like using these cyan pencils. I keep all the pencils on there, I don’t have to do any weird stuff.

DB: You don’t have to erase it and smudge it.

RCS: Yeah, no. This must be interesting to people who make comics, or whatever. I don’t know how many crazies, but I think it’s great.

DB: You do it a slightly different way to a way I know, because you can work in pretty much any colour you like. Then if you open up the channel mixer, so Image Adjustments – Channel Mixer, and you’ve got a bunch of pre-sets, so you can do black and white with blue, or black and white with a green.

RCS: Oh, I don’t know how to do that actually.

DB: Oh, it’s good. I can only think about it in CMYK. I can’t think about it in RGB.

RCS: I know, same.

DB: CMYK for print, for the listeners, and RGB for screen. Of course. Everyone knows this.

RCS: Right.

DB: Then you can say, alright, I’ve drawn everything with blue and then inked with black over the top, or pink or whatever colour, and then you can choose that particular pre-set, and then just nudge the sliders up and down, bring the black up, take the cyan or magenta down, and you get this really nice… get rid of all that colour and you’re just stuck with your black lines. You’re welcome, internet!

RCS: Yeah.

DB: It’s a really neat way of working.

RCS: I didn’t follow that, but I might rewind the podcast and hear that, but basically yeah, it’s the same deal. I use the cyan pencils, I can get rid of the pencils and then nowadays, I definitely edit stuff on the computer. But it is true that for me it’s hard to feel really excited about something I made… like, if I’m doing this thing where I’m going on a computer to fix drawings, that usually feels bad. If I’m on my game, you know, if I’m going into the computer to just change drawings, that means I’m off my game, and I know it. If I’m doing well, I draw it with pencil and I’ll definitely make small corrections, but if I’m going back in to draw stuff on the computer… this is just for me, but…

DB: No, that makes sense to me. The thing that I’ve noticed is that if I don’t make big corrections to what I’ve drawn, no one notices that I’ve made mistakes. But if I do make big corrections to my mistakes, people notice that I’ve made mistakes, so they become visible by correcting them almost.

RCS: Oh, Jesus Christ.

DB: It’s really strange for me. I know I have this loose style that lends itself to having a way with lines I guess.

RCS: I’m doing a book right now, so if you can catch the mistakes then I will… I’m going to ask you to check, see if you can find where they are. That’ll be the test.

DB: I’ll treat it like a book of crossword puzzles.

RCS: Yeah, just be like, ‘Oh he definitely edited that!’

DB: [laughs]

RCS: Obviously editing, there’s nothing wrong with that. It’s not all perfect. I mean, I feel fine adding drawings on computer if I have to, but hopefully I don’t have to. Then usually for me, in my case, it’s just a matter of locking down all the greyscale to make sure the line art is right. If I’m going to colour it, I do all that. It’s so boring doing colouring, it takes so long, but you gotta do it.

DB: Yep, if you want colour comics, you’ve got to colour comics.

RCS: Right, if you have to, which you don’t have to.

DB: Sure.

RCS: Then I don’t know. If we’re talking about making a book, which is usually what I’m doing, then at this point I’m pretty much getting everything ready to be in the printer layouts and stuff. At this point I’m also definitely thinking about how much it’s going to cost, how many pages.

DB: How far ahead do you cost things? Do you estimate weights for postage?

RCS: Usually I think about how much it’s going to cost to ship something. Sometimes I just include free shipping to make it simple on myself. If I know it’s going to cost this much, I’ll just include that in the price and just call it free shipping. What I’d rather do… the reason I don’t have to think about shipping so much in the beginning stages, is what I’d rather do is… the rule of thumb is to charge four times what it cost to put it together, because when I wholesale it at stores, I usually sell it to stores for 50% of the retail price. So if I’m selling a book for five bucks, that means that I get $2.50, so if it cost two bucks to make, I’m making 50¢ off the book, and that’s garbage, you know? So you’ve got to adjust the prices, right? Usually what I’m thinking is, ‘It costs this much to make, I’ll charge this much, and then I’ll pop shipping on top of that.’ But recently I’m figuring out a book where shipping’s going to be weird, so in that case I might just include the shipping with the retail price, because it’s just so complicated to ship it.

DB: All these things that a young cartoonist doesn’t ever think about.

RCS: Yeah, I mean, you just think about it once you start actually doing it, and then, yeah, it becomes a big part of thought, but I like thinking about this stuff.

DB: Yeah, me too. Okay, let’s talk risograph.

RCS: Alright. Well, I was just saying to you off mike, that, um…

DB: This is us dropping back in again.

RCS: Yeah, is that I don’t like that risograph gets overhyped a little bit, because you were telling me about this ComColor Express, which is like a risograph that does CMYK, and I thought, ‘What is this? I’ve gotta know about this,’ because I do kind of CMYK stuff, and what I always say about it is like, you know the risograph can’t really do CMYK because the registration is not going to be good. They’re not made to do perfect registration. What I have now erroneously told people is that risograph wouldn’t make a CMYK printer because they’re going to be disappointed by the results, so what is this ComColor thing? Does it look good?

DB: It looks pretty good. Well you know how your original… let’s call it original risograph.

RCS: Yeah, your basic risograph.

DB: So for people who don’t know what this is, it’s somewhere between photocopying and screen printing.

RCS: Basically it’s like a photocopier. It looks like a photocopier exactly, it just has a different method inside. So the method inside that it prints by, basically you don’t get greyscale so much. It’s more black and white. And the really good ones can get really fine tuned, but the thing is you can do it in any colour. Instead of doing it black you can do it in whatever colour you can get from the risograph company.

DB: Gold.

RCS: Bright orange or gold, or whatever. Gold is a cool one if you can get it.

DB: Yeah, I’ve seen that. It looks very nice.

RCS: My Style and Fashion Zine has gold, and some other people have gold too. It’s pretty cool.

DB: That was I think the first place I’ve seen it in the flesh, and I like it.

RCS: It’s pretty cool, right?

DB: Yeah! Pretty cool isn’t really selling it enough, it’s very cool.

RCS: It’s very cool, but it’s hard to work with, but you know, you’re right, it can be really, really cool. It’s interesting. Anyway, you were saying the risograph is a basic… like a photocopier. Kind of like a screen printer. I think that’s saying too much. Good screen printing looks great, risograph is not that.

DB: My problem with it initially, because I was very snippy about risograph to begin with, is that it became this cool thing, and then you’d have people saying, ‘Oh yeah, we’ve got some risoed things.’

RCS: I absolutely agree with you.

DB: It was a lot of varnish on not a lot of wood, if you know what I mean.

RCS: Yeah, a lot of varnish on a lot of wood. [slam] I love it. Sorry, I slammed the table there.

DB: [laughs] People like the [slam] passion! There we go, I did the same. I got kind of snippy about it, until I realised, ‘Oh, this is a very affordable way of printing a lot of stuff pretty quickly.’

RCS: Yes, exactly! Very true! Very good. That’s exactly right. There’s a lot of varnish on a lot of wood where people are like, ‘Oh, it’s a risograph, blah, blah, blah,’ but the great thing about risograph is that, yeah, it’s an affordable way to make work that looks good. So if you can get it, you know, compared to doing a photocopy, another thing is, I mean, I’m not saying a photocopy looks bad.

DB: It can look really bad.

RCS: Well, I want to say that, like, here’s the thing. I think that a bad risograph doesn’t look better than a bad photocopy necessarily, although it might. You might argue that. But what I definitely say is that everyone in their normal life in the UK, and in America and in most places has lived their life seeing bad photocopies, bad inkjet prints, bad laser prints, and you know what that is and your mind reads that object as a bad laser print. But when you see a risograph, you’re like, ‘Wait, what is this?’ It looks weird.

DB: ‘I don’t have much context for this.’

RCS: Yeah, so even if it’s done bad, you’re like, ‘What is this weird thing?’ It looks different, so it looks cool, you know?

DB: Yeah, exactly that.

RCS: It does look cool, but on the other hand, bad risograph looks bad. And it’s good to just make it whatever way, but this ComColor thing you said looks good. I’m so bad, I’m looking at my phone right now. I’ll have to check it out. I do like, fake… I call it faux CMYK where I do… what I’ll do is I’ll do a test print of different hues and different colour mixes, and then I’ll go into that test print and I’ll look at it and I’ll pick the colours to figure out how I did it. So it’s kind of like working backwards to do a proof. The thing about that method is number one, the colours are not a complete spectrum, it’s limited.

DB: It’s like a photograph from the early 1980s.

RCS: It’s like a photograph of a photograph. It’s like a photograph of the early 1980s, and the photograph is old. It’s like an instant photo. Of course it’s off register a little bit, that’s always a thing, and the spectrum is narrower, but if you work it, if you think about it, just like anything, you can make it look really cool. I’m constantly trying to figure out how to do it, and I’ll look at something and be like, ‘This is actually not that cool.’ And notice something that is pretty cool, like I did a bunch of scans of markers in the Style and Fashion Zine where I just straight scanned markers and spit them out. I don’t have CMYK colours with my risograph, but I use a light blue, and the pink is the one that always gets weird. I use different types of red. If you look in the Style and Fashion Zine you’ll see pages where I’ve printed in pink, and the cover is printed with a red for the CMYK, the M, magenta, it’s actually like an orangey red. But then if you look at, I think page three, that’s done with a bright pink, which is a cool colour. So I try different inks to go into that CMYK process, but it’s always going to look weird. And I always think that if someone approaches doing CMYK… I’m really interested to see this ComColor Express thing because on the one hand I think that’s cool. I mean, I’m instantly like, ‘Oh, I gotta see this,’ but on the other hand, and this is my real feeling is, like, if someone just approaches it just to print CMYK, just to print it, it feels so joyless and not interesting. But I have to see it. Oh please let it be really cool. Listen to me, I’m being snippy about the thing that I do, because I put so much into it, and now you’re talking about that printer that does it automatically. Listen to me, you can hear me being a jerk!

DB: The other thing that we were talking about off mike was that I bought a risograph machine so that I’m more in control of the overall process, and I don’t have to pay for print runs. I realised that if I took the money that I would spend on one or two print runs, I could buy myself a print press.

RCS: Totally man, totally man. That’s totally true.

DB: It’s the same with this ComColor thing. We can get this four colour riso separations for the cost… well, of more print runs, but then I’d be able to do more print runs myself.

RCS: But why would you want to do CMYK? That sounds like such a… so stupid. Why would you want to do four colour CMYK? The thing is, that’s a question. I’m not saying you shouldn’t, I’m saying why would you want to do that? The tone of my voice is, I don’t think you should do that, but it’s a real question. It means if there really is a good use for that, good.

DB: I guess for me, it’s replicating the work, because it’s all painted, I guess is then taking those colours from my sketchbook or on the paper I’ve painted on, and then replicating them.

RCS: Yeah, but what if it’s a bad replication? So, then what? I don’t know.

DB: Yep, it’s a good question.

RCS: I don’t know, it’s compelling.

DB: This is the eternal struggle of the artist.

RCS: Yeah, it’s fun to think about. It’s fun to think about but I… um… what should I say? What can I say? Hmm. Sorry.

DB: [laughs]

RCS: I’m at a loss for words because… yeah… I guess I’m just… hmm. I’m trying to think of a finisher for that, but I don’t know what to say. I want to… I love thinking about this stuff. I’m kind of annoyed when people think there’s more magic to it than there really is, but on the other hand the results are real. The great thing about risograph isn’t even just the results, it’s like what you said, it’s the fact that it lets you do things that would be really hard to do. I actually think that if I hadn’t found risograph, and hadn’t found this great way to print the things that I do at a reasonable price with good results, then honestly maybe I would be doing different work, and maybe it would be easier for me to get hired for other freelance work, because I wouldn’t be obsessing over this stupid risograph stuff so much!

DB: [laughs]

RCS: You know, risograph looks really good, when I print it, the way I print it, but if I didn’t have that then I would probably get my work and look at it and be kind of disappointed with how this came out. Then, I would probably try to do something more financially rewarding.

DB: Yes.

RCS: So that’s a dilemma, and I am interested in this dilemma.

DB: I don’t think we’re going to arrive at any resolutions today.

RCS: No man, sorry.

DB: We’ll table it for another day I think. So how do you then advertise yourself?

RCS: Well, I use Instagram a lot, and I feel like I recently, I just put it on Instagram. I post my process on Instagram so people see that I’m working on something, and I just assume that those people also see Tumblr. Or I’ll announce it then on Instagram, and I’ll announce it on Tumblr, and recently I haven’t been updating my main website, which is so lame. You know, for Christ’s sake, there’s so much stuff to update.

DB: What more do you want, people?

RCS: Yeah. So I’ll usually announce it on Tumblr and Instagram and Twitter, and that’s a lot of people who see that. You get some Retweets from friends and stuff, and that’s good, and then… how do you advertise stuff? I try to get stuff out to reviewers, but I don’t know what I expect from that, you know? So it helps, and I’m also kind of really bad at it. I’m trying to get better about it, but I think it’s good to get people out. I don’t know, I’m grasping at straws here. How can I get promotion? Because basically it’s like, I think the work is really good. I feel great about the work I made, and people just don’t know about it yet, so I’m just trying to like…

DB: You’ve got to work to that assumption that people are going to be into it as well, don’t you?

RCS: Well, I’ve got it. I made it. I feel like I like the work I do. So I feel really great about it, so I just want to get people to know about it. So I try to send out review copies and, I don’t know, that’s all I do. I send it to stores, that’s the other thing. I send it to stores, and so I think that helps. I wish… you know, it’s great when I hear someone on Twitter say, ‘I bought your books. I bought Ryan Cecil’s books at this store.’ I feel awesome, because it’s great for that store too, because I feel really bad if I send something to a store and they don’t sell. I’m so happy if someone buys my stuff from a store, because it means that store didn’t lose money buying my stuff. It’s like, okay good. They feel good about that, thank goodness.

DB: Retail works!

RCS: I mean, it works for them. I want it to work for them. I don’t want them to feel dumb for buying my stuff. So through those things, I don’t know, you Retweet stuff, and I’m just one person, so I do odd stuff in fits and starts as I can.

DB: You don’t have a staff working for you.

RCS: Nope!

DB: None of us do! So what have you got coming up then?

RCS: Well, I won’t tell you what’s coming up, because actually I haven’t announced it yet. But I’ll tell you what I just finished. I mean, I never talk about what’s coming up, so maybe this is why I’m bad at publicity. I like to announce it when it’s ready, because I’m not sure if it will mess up on the way. The project that I just started working on that’s new is called Style and Fashion Zine. It’s not really a comic book, although I think issue number two is going to be more than half comics, unlike the first one. It’s like a zine that I made… see, when I was in LA for a while, I was in LA for a few months away from Japan, and I really missed the fashion and the personal style and the world of communication through clothing that happens in Japan. It’s just amazing and beautiful here, I love it, and I really missed it when I was there. One dumb way to say that is like, ‘Everyone dresses like slobs,’ or something, but that’s not it.

DB: Everyone dresses like Dan Berry!

RCS: Notice I didn’t actually…

DB: No you didn’t endorse that.

RCS: I also didn’t defend you from that joke.

DB: [laughs]

RCS: I’m such a jerk.

DB: Neither confirm nor deny.

RCS: Because that’s not the point. The point is, I just love this big world of the way people dress. It’s really cool. It’s a different culture. I mean, it’s not our culture, the way people care about these things. So it’s been so fun, it’s so beautiful. I miss it, so when I came back I decided that I would make this zine, to be the kind of thing that I wish I could read when I wasn’t in Japan. So I want to write about what’s trending. Maybe that’s a superficial thing to say, but for me it’s just so fun to see what people are wearing. It’s sometimes quite bizarre to see what becomes popular, and it’s fun to catch it as you walk around and be like, ‘I see metallic shoes all the time now.’ And that’s a real thing, you know, I see metallic shoes all the time. So I’m making a zine about that, so I have issue one out. Issue two, we’re trying to do it monthly.

DB: This is the sound of issue one. [rustling paper]

RCS: Yeah, well that’s the sound of it, but it looks real good too. I would say it’s… you know, I’m kind of aiming it… I haven’t done a project like that before. I usually always do comics. It’s kind of for people who are into fashion or into Japan.

DB: And drawing I would say.

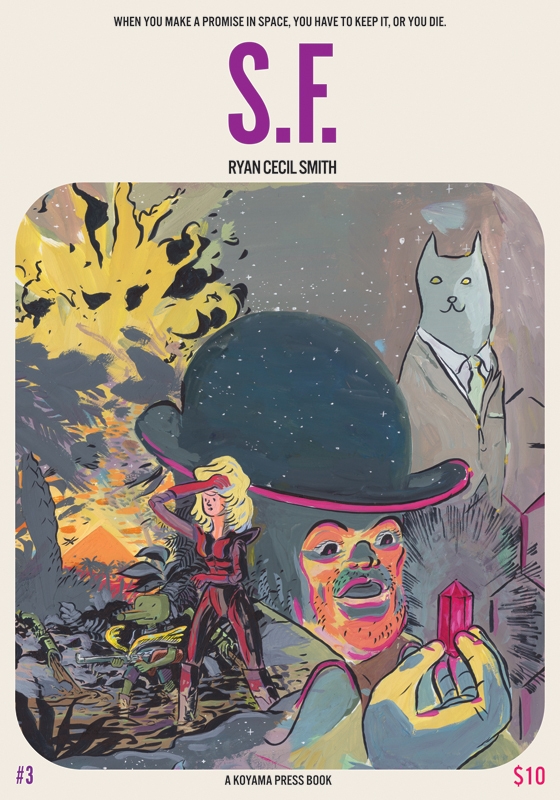

RCS: And drawing, yeah, because that was a rule also, no photographs. That would be a bit of a mark of distinction. It’s not about photographs of clothes. So that’s a new thing I’m doing, and I’m always doing… I have my main series, which Annie Koyama publishes, it’s called S.F. and that will… she published number three. She’ll publish number four in an unspecified date. But in between I’m always making small books based in that universe. The newest one is called… oh, it’s my web series on this website, Hazlitt. So I do a web series for them, so for a couple of zine fairs I’m going to make a mini comic book, and I have some other things like that. I also do these looping comic books for an animation festival thing called LoopDeLoop. It’s this bi-monthly animation challenge for students or professional animators, both really. Or just hobbyists or whatever who want to do something small for themselves. What they do is they put out this call for looping animations. If you can make a walk cycle, or something longer, and they give it a theme every two months and people submit their animations they make in all different ways. They go up on their website, they get screened in cities around the world. This time they had Paris and Melbourne and LA. It’s kind of a cool thing, and when I was talking to somebody about it, I was like, ‘What is the zine version of that? I would be like…’ and what I do, it would have no ending and no beginning. So I put the zines together in a way where there’s no defined end or beginning, and the story can start and begin at any point. For me this is a fun exercise to think about, ‘How can I do this cool thing?’ I made a bunch of those too, those are really neat.

DB: The never ending palindrome.

RCS: I want to promote those. I’ll shut up, sorry.

DB: Those are on your Big Cartel?

RCS: Yeah, thanks. I just wanted to say that’s what I’ve been working on, so it’s kind of neat, but whatever.

DB: Whateva!

RCS: I’m not trying to push people to do what they don’t want to do.

DB: I am. You should go and do this listeners. Go and do it right now! Give your hands and eyes a treat, and your ears too.

RCS: Thanks Dan!

DB: So, where is the best place for people to go? If they’re listening to the podcast right now and they think, ‘Cripes, I want to buy this guy’s stuff,’ where should they go?

RCS: Well, my Tumblr is Screentone.TV. I have a TV domain for no reason. And really the best place to get my stuff is my Big Cartel website, which is screentonetv.bigcartel.com. That of course has a link to my Tumblr where I talk about the work more, all the process posts or whatever, but that has all the books up there. Those books are shipped from either Japan or America in batches. And if someone’s listening to this, and I didn’t send your order out already, and you’re thinking that I am a huge jerk, then just tell me. I’m really sorry. I am sorry. Please, I welcome your email to tell me, and I’m not trying to gyp you or anything. I feel like whenever I talk about my work I have to say that.

DB: [laughs] This disclaimer!

RCS: Yeah, sorry.

DB: That’s fine. I mean, it shows you care.

RCS: They don’t think I care, cause I didn’t send their book out for a long time.

DB: Well, you know. You’re just one guy. Blame your staff. It’s your admin team.

RCS: You know, actually I do have a…

DB: It’s the fulfilments department, it’s their problem.

RCS: I do have one staff member, my mailing operations manager back in North Carolina. My M O M, ships some books out for me.

DB: [laughs]

RCS: I can’t throw her under the bus, you know? That feels bad. I can’t… it’s my fault. I can’t blame the staff.

DB: Okay, it’s all on you. So if you’ve got hate mail you want to send Ryan, they should just Google you, or they can send it to Twitter?

RCS: Yeah, I’m on Twitter, @ryancecil and on Instagram also, so if someone wants to ever say something to me, like, ‘Hi,’ I will say hi back. I don’t know, I’m on those all the time.

DB: Give it a shot listeners, see what happens! Well Ryan, thanks very much for speaking to me.

RCS: You’re welcome!

I love his drawing style. To me he’s the cartoonist’s cartoonist.